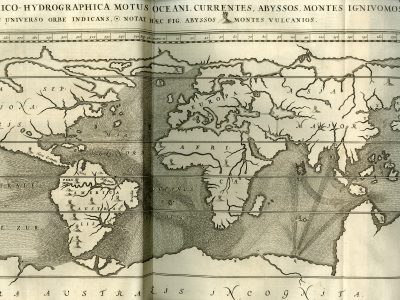

Tabula geographico-hydrographica

Athanasius Kircher, De onderaardse Wereld (Mundus Subterraneus), 1665 (1682)

Title of the volume: De onderaardse Wereld (The Subterranean World)

Date: 1682

Author: Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680)

Engraver: Theodor Matham (1605/06–1676)

Printer: Joannes Janssonius van Waasberge

Publisher and Place of Publication: Joannes Janssonius van Waasberge, Amsterdam

Plate execution tecnique: Chalcography

Language: Dutch

Location: Geography Library, Morbiato Collection, MORB.15.

Notes on the volume: Athanasius Kircher, born in Geisa, Thuringia, in 1602, was an extraordinary scholar and an excellent popularizer of knowledge. The freedom to devote himself continually to his research—which spanned philology, natural sciences, mathematics, physics, astronomy, music, medicine, and more—was made possible by his entry into the Society of Jesus in 1618, which supported him financially and logistically. From his fellow Jesuits stationed around the world, he also obtained numerous reports on distant lands, the collection of which constitutes one of his major contributions to geography. In 1634, he moved to Rome, where he remained until his death. There, he taught mathematics at the Collegio Romano and, in 1651, founded a famous museum modeled after a Wunderkammer, which housed ethnographic, archaeological, and natural specimens, along with machines he himself had designed for research and amusement. The Mundus Subterraneus (The Subterranean World), first published in Latin in 1665 in Amsterdam, is a treatise in 12 books dedicated to phenomena occurring beneath the Earth’s surface. According to Kircher, the Earth is internally traversed by networks of fiery cavities (or magnetic chambers) and hollow channels containing water, forming a closely interconnected system. His cosmic vision, influenced by Neoplatonism and Hermeticism, aims to harmonize scientific explanations of phenomena with religious teleology. On one hand, his theories are supported by experiments, such as in the fifth book where he explains the phenomenon of water rising using an experiment of his own design, involving a machine made of two bellows and a water-filled container. On the other hand, Kircher interprets this and other phenomena as manifestations of Divine Providence that make life on Earth possible. The volume is accompanied by numerous plates illustrating geological phenomena, sometimes based on the author’s direct observations. This is the case, for example, with the plates depicting eruptions of Mount Etna and Vesuvius: Kircher personally witnessed the eruption of Etna, as well as Stromboli, during his journey through Sicily and Calabria in 1637–1638. On the same occasion, he descended into the crater of Vesuvius to observe its condition after the 1631 eruption.

GEO-CARTOGRAPHIC DATA

Scale: approx. 1:73,000,000

Graphic scale: –

Orientation: North at the top

Size: 54 × 30 cm

Descriptive notes and regional divisions: This is a planisphere that, as the title suggests, particularly highlights ocean currents and the distribution of abysses and volcanoes. These three types of information are identified through specific symbols incorporated into the title itself, which thus also serves as a legend. The margins are marked in 10° intervals, and the tropics and the equator are emphasized with bold lines. The projection is based on Mercator’s (1569), though it appears more stretched along the west-east axis. This map is historically significant as the first known map to outline—albeit in a preliminary form—ocean currents. America, Japan, and Korea are depicted with low accuracy due to the limited information available at the time. New Guinea is shown.

In Africa, the courses of the Nile and Senegal/Niger rivers are marked, along with the presence of three volcanoes—two in the Sahel region and one along the southwestern coast. No other reliefs, regional divisions, or place names are present, except for the names of continents and oceans. In the second book, Kircher focuses in particular on the Mountains of the Moon in central Africa, then believed to be the source of the Nile. Within a map of the southern part of the continent, he presents a longitudinal section showing a large underground lake within the mountains that feeds the river. In addition to Greek tradition, Kircher’s sources on Africa include the writings of Jesuit missionary Pedro Páez, who spent many years in Ethiopia in the early 17th century.

Bibliography

Badino G. (2016). Il vento ipogeo: una storia delle prime osservazioni. The underground wind: a story of the first observations. Atti e Memorie della Commissione Grotte “E. Boegan”. 46: 31-70.

Luzzini F. (2013). Il paradosso di Kircher (che paradosso non è). Acque sotterranee – Italian Journal of Groundwater. 2: 65-66.

Morello N. (2002). La Rivoluzione scientifica: i domini della conoscenza. Le scienze della Terra. In: Storia della Scienza, Roma, Treaccani.

Parcell W. (2009). Signs and Symbols in Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus. In: Rosenberg G.D., ed., The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to Enlightenment. Boulder, The Geological Society of America: 63-74.

Tacchi Venturi P. e Almagià R. (1933). Kircher, Athanasius. In: Enciclopedia Italiana. Roma, Treccani.

Viglas K. (2014). Η Αναλογική Σκέψη του Αθανάσιου Κίρχερ ως Βάση Σύνδεσης του Ολισμού με τον Νεοπλατωνισμό (Athanasius Kircher’s Analogical Thought As The Basis of the Connection Between Holism and Neo-Platonism). Philosophia E-Journal of Philosophy and Culture. 8: 3-28.