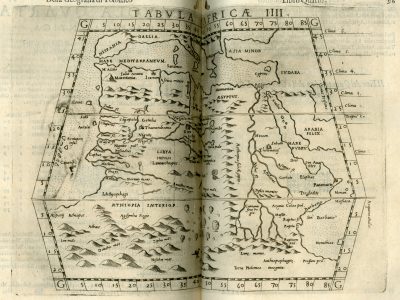

TABVLA AFRICÆ IIII

Giuseppe Rosaccio, Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo alessandrino, tradotta di greco nell’idioma volgare italiano da Girolamo Ruscelli, et hora nuouamente ampliata da Gioseffo Rosaccio, 1599

Title of the volume: Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo alessandrino, tradotta di greco nell’idioma volgare italiano da Girolamo Ruscelli, et hora nuouamente ampliata da Gioseffo Rosaccio, … et vna Geografia vniuersale del medesimo, separata da quella di Tolomeo; … Et vna breue descrittione di tutta la terra, distinta in quattro libri, … Con due indici copiosissimi di tutto quello, che di notabile si contiene nell’opera (Geography of Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria, translated from Greek into the Italian language by Girolamo Ruscelli, and now newly expanded by Gioseffo Rosaccio, … and a universal geography by the same, separate from that of Ptolemy; … and a brief description of the entire Earth, divided into four books, … With two very comprehensive indexes of all noteworthy content in the work)

Date: 1599

Author: Claudius Ptolemy (ca. 100 AD – ca. 175)

Other authors: Giuseppe Rosaccio (ca. 1530–1621), Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566)

Publisher and place of publication: Eredi di Melchiorre Sessa, Venice

Plate execution tecnique: chalcography

Language: Italian

Location: Geography Library, Morbiato Collection, MORB.7

Notes on the volume: Starting from the 15th century, the dissemination of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia marks a new cultural phase in the history of cartography. This was made possible by the translation of the text from Greek to Latin by Jacopo Antonio da Scarperia in 1406; the maps, however, reconstructed based on the Greek text by Maximus Planudes in 1295, followed a separate tradition. The first printed editions appeared in the last quarter of the 15th century, with cartographic elements added only later. Ptolemy became an authority for Western cartographers, who found in his text solutions to projection problems thanks to its astronomical, mathematical, and geometric information. However, his data was also increasingly questioned and corrected in light of the discoveries produced during the vibrant era of exploration. Nevertheless, some inaccuracies of the Alexandrian astronomer persisted for centuries—for instance, his overestimation of the Mediterranean’s longitudinal extent from 42° to 62°, which distorted the coastal outlines. This error was only corrected with Guillaume Delisle’s pivotal map of Africa in 1700.

The first Italian edition of Ptolemy’s Geography was published in Venice by Giovanni Battista Pederzano in 1548, translated by Pietro Andrea Mattioli with maps engraved by Giacomo Gastaldi. In the preface “To the readers” of the edition under discussion, Rosaccio specifies that the translation of the first chapter should be credited to the Venetian humanist Girolamo Ruscelli, while the rest follows Mattioli’s version. Rosaccio also intervened in updating the place names shown on the maps.

The edition, dedicated to Marco Pio of Savoy, Prince of Sassuolo and Duke of Ginestra, in fact includes three separate works: the Ptolemaic edition proper, Rosaccio’s own Descrittione della Geografia Universale (Description of Universal Geography) in four books, and Espositioni et introdutioni universali di Girolamo Ruscelli sopra la Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino (Universal Expositions and Introductions by Girolamo Ruscelli on Ptolemy’s Geography).

GEO-CARTOGRAPHIC DATA

Scale: –

Graphic scale: –

Orientation: North at the top

Size: 25.5 x 18.5 cm (plate impression)

Descriptive notes: This is the fourth and final map depicting Africa. All four borders are marked with graduations at 5-degree intervals. Vegetation zones are highlighted using small tree illustrations. Between the equator and the latitude of northern Italy, there is a division into six climate zones, numbered along the right margin. Near the lower right edge, south of the Mountains of the Moon, the inscription “Terra Ptolomeo Incognita” (“Land Unknown to Ptolemy”) is visible. The portion of Africa shown is divided into the three principal regions of Aegyptus, Libya, and Interior Aethiopia. Relief is depicted using the typical “molehill” technique, but unlike other maps, this one includes a rich set of place names. Regarding hydrography, the Nile’s sources are located in the Mountains of the Moon. A main river rises from Mount Thale in the center of the continent and flows westward under the name Niger River until it reaches a lake located above the Nigritis swamp. From this lake, it continues under the new name Massa River to the ocean. The maps in this volume feature many animal illustrations, both in the seas and on land. In this particular map, there are two snakes coiled in different ways, a lion, and a griffin (the latter hard to see because it’s placed along the page fold). These creatures are drawn from medieval bestiaries known to have circulated in various northern Italian courts.

Bibliography

Bernardinello S. (1997). Le carte dell’Africa nella Geographia di Tolomeo, lettura dal codice Marciano gr. Z. 516. Padova, La Garangola.

Casali E. (2017). Rosaccio, Giuseppe. In: Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Vol. 88. Roma: Treccani.

Cusimano G. & D’Agostino G., ed. (1986). L’Africa ritrovata. Antiche carte geografiche dal XVI al XIX secolo. Palermo, Quaderni del “Servizio Museografico” della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia dell’Università di Palermo.

Procaccioli P. (2017). Ruscelli, Girolamo. In: Dizionario bibliografico degli italiani. Vol. 89. Roma: Treccani.

Van Duzer C. (2012). I mostri marini nel manoscritto di Madrid della Geografia di Tolomeo (Biblioteca Nacional, MS Res. 255). Geostorie. Bollettino e Notiziario del Centro Italiano per gli Studi Storico-Geografici. 20/1-3: 113-132.